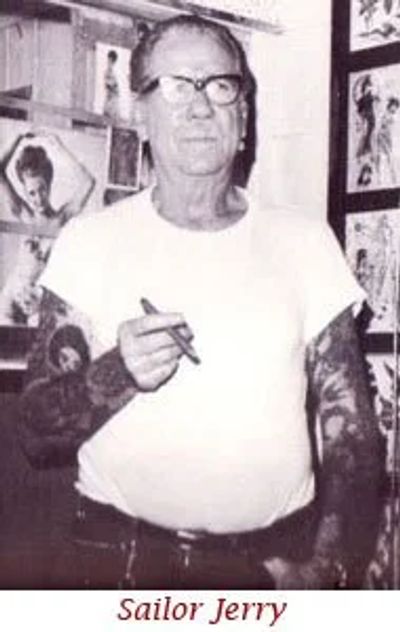

THE LEGACY OF SAILOR JERRY

The Architect of American Traditional Tattooing

Norman Keith Collins, born January 14, 1911, in Reno, Nevada, became Sailor Jerry, the legendary figure who defined American traditional tattooing. As a teenager, he hitchhiked and hopped freight trains across the U.S., learning to tattoo with a needle and black ink, working freehand one poke at a time. In Chicago, he trained under Gib “Tatts” Thomas, mastering the electric tattoo machine by practicing on locals, sometimes paying with cheap wine or small change. His Navy service exposed him to Japanese irezumi, the intricate full-body tattoos that inspired him to blend their precision and vibrant colors with the bold, simple imagery of American tattoos.

After the Navy, Collins settled in Honolulu during WWII, setting up shop on Hotel Street, a gritty hub of bars, brothels, and tattoo parlors packed with sailors and soldiers on shore leave. His tattoos—anchors, swallows, pin-up girls, ships, dragons, snakes, hula girls, koi fish, skulls, roses, dice, and nautical stars—captured the pride, bravado, and adventure of wartime life. Designs like “Man’s Ruin” (a woman in a cocktail glass with dice and cards) and “Death Before Dishonor” (a knife through a heart) reflected the raw truths of his clients’ experiences. By fusing American traditional’s standalone symbols with Japanese tattoos’ flowing, narrative style, he created a distinctive look: clean, bold lines with vivid colors and deep meaning.

Sailor Jerry revolutionized tattooing beyond artistry. In an era with limited ink colors (black, red, yellow, green), he worked with chemists to develop the first reliable purple ink, a game-changer he flaunted by sending clients to rival shops to show it off, sometimes with a bouquet of purple orchids for added cheek. He pioneered safety standards, being among the first to use single-use needles and autoclaves, ensuring hygienic practices in a time when tattoo parlors were often unsanitary. He also created custom needle formations that embedded pigment with less skin trauma, enhancing both quality and comfort. Fiercely protective of his craft, he refused to ink large chest or back pieces over tattoos by “brain picker” artists he deemed inferior, and he corresponded regularly with Japanese masters, sharing techniques and tracings to refine his work.

Outside tattooing, Collins was multifaceted. He captained a three-masted schooner, hosted a radio show called *Old Ironsides* on KTRG, alternating between political rants and poetry readings, played saxophone in a jazz band, and worked as an electrician to innovate his tattoo machines. He rode a Harley and a canary-yellow Thunderbird, embodying his rebellious spirit. His competitive nature shone through in his letters to fellow artists, obsessing over shading techniques, tone, texture, and “crash” effects, always striving to improve. He once wrote, “I haven’t done my best yet, only my best so far.”

Collins died on June 12, 1973, after a heart attack. Characteristically defiant, he rode his Harley home after collapsing. He left instructions for his shop at 1033 Smith Street in Honolulu’s Chinatown to pass to protégés Ed Hardy, Mike Malone, or Zeke Owen—or be burned down. Malone took over, running it as China Sea Tattoo for nearly 25 years. Earlier studios included 434 South State Street and 13 and 150 North Hotel Street. Collins was survived by his fifth wife, Louise, and four children, and is buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

His legacy endures. Apprentices Hardy and Malone carried his style forward, making it a cornerstone of modern tattooing. His flash, featuring sailing ships, wildcats, eagles, falcons, swallows, motor heads, pistons, and classic scroll banners, has been exhibited at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris and the Field Museum in Chicago. The annual Sailor Jerry Festival in Honolulu, started in 2015, celebrates his influence with music, art, and tattoos, donating proceeds to his family. In 1999, Hardy and Malone partnered with Sailor Jerry Ltd. to license his designs for clothing, ashtrays, sneakers, playing cards, and a 92-proof spiced rum featuring his hula girl artwork. In 2019, Louise sued the rum’s owner, William Grant & Sons, over unauthorized use of his name and imagery, settling in 2020. A 2008 documentary, Hori Smoku Sailor Jerry, chronicles his life.

Sailor Jerry’s contributions—innovative inks, custom needles, safety standards, and a bold, cross-cultural style—transformed tattooing into a respected art form. His work remains a testament to living and creating outside the lines.