HISTORY OF TATTOOING

Just something cool I put together on the history of tattoos. It touches on where tattooing started, how different cultures have used it, and how it grew into the tattoo culture we know today.

There’s definitely more out there on the subject, but this gives a quick look at the roots and evolution of tattooing. Thought it was worth sharing.

Tattooing

The art of embedding ink into the skin to create permanent designs

Tattooing is one of humanity’s oldest forms of expression, spanning over 5,000 years across cultures and continents. From therapeutic markings to symbols of status, spirituality, and rebellion, tattoos have served diverse purposes throughout history.

The evolution of tattooing, beginning with its earliest evidence in prehistoric times, tracing its cultural significance through antiquity and the modern era, and concluding with contemporary styles like New School and emerging trends. By examining tattooing’s historical, cultural, and artistic developments, we uncover its enduring role as a medium of identity and creativity.

Ancient Beginnings

THE EARLIEST TATTOOS

The origins of tattooing date back to the Neolithic period, with the earliest evidence found on Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,300-year-old mummy discovered in 1991 in the Ötztal Alps. Ötzi’s 61 tattoos—lines and crosses near joints—aligned with acupuncture points, suggesting a therapeutic purpose, possibly for pain relief from arthritis or digestive issues. This predates documented acupuncture in China by 2,000 years, indicating tattooing’s medicinal roots.

In ancient Egypt (circa 2000 BCE), female mummies, such as Amunet, a Priestess of Hathor, bore dot and dash tattoos linked to fertility, protection, or religious devotion. Bronze tools from Gurob, Egypt (1450 BCE), are considered early tattooing implements. Nubian mummies displayed blue geometric tattoos, while Scythian Pazyryk mummies from Siberia (6th–2nd century BCE) showcased intricate animal and mythical designs, reflecting status and cultural identity.

In Polynesia, tattooing, known as tatau or tā moko, was a sacred practice. Elaborate designs covering large body areas signified lineage, status, and spirituality. In the Philippines, batok tattoos among indigenous groups like the Kalinga symbolized bravery and tribal identity, a tradition upheld today by Apo Whang-Od, a 106-year-old mambabatok.

Tattoos in the common era

In ancient Greece and Rome, tattoos often marked social status—negatively. Greeks used tattoos to brand slaves and criminals, a practice Romans adopted, calling them “stigma.” However, some Greeks, like Ptolemy IV, embraced tattoos as devotional symbols, such as ivy leaves for Dionysus. In contrast, Thracians and Scythians viewed tattoos as noble.

With Christianity’s rise, tattoos gained religious significance. Early Christians, including Crusaders in the Middle Ages, tattooed crosses on their hands or arms as symbols of faith and pilgrimage. Despite Emperor Constantine’s ban on tattoos due to their pagan associations, these religious markings persisted, representing devotion and identity.

In Asia, Japanese irezumi evolved from punitive markings to an art form among samurai and civilians by the 19th century, featuring mythical creatures and nature motifs. In China, ci shen tattoos served both punitive and protective roles, blending punishment with spiritual significance.

The Modern Era

Sailors, Socialites, and Stigma

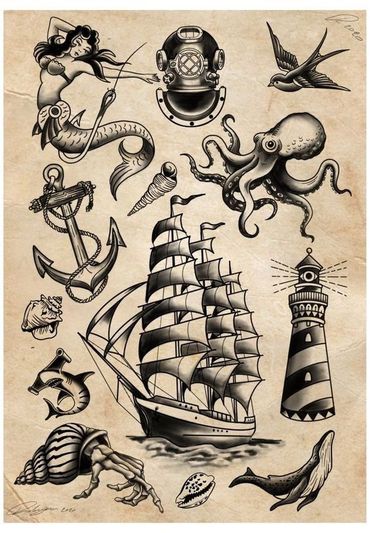

Tattooing gained prominence in the West during the 18th century, spurred by European explorers like Captain James Cook, who encountered Polynesian tatau in Tahiti in 1769. Sailors adopted bold, nautical designs—anchors, swallows, and pin-up girls—laying the foundation for American Traditional tattooing. Samuel O’Reilly’s 1891 electric tattoo machine revolutionized the practice, making it faster and more accessible, though it initially lowered its elite status.

In the 19th century, tattoos became fashionable among European and American aristocracy. British royals like King Edward VII and King George V sported tattoos, inspiring socialites like Lady Randolph Churchill, who wore a discreet snake tattoo. Cosmetic tattoos, such as permanent eyebrows, emerged in the 1920s as practical beauty solutions.

Despite this, tattoos carried a stigma, associated with sailors, criminals, and circus performers. During the Holocaust, the Nazis tattooed numbers on Auschwitz prisoners, a dehumanizing practice. In the 1930s, some Americans tattooed social security numbers for identification, though this remained uncommon due to social disapproval.

The Tattoo Renaissance

Mid-20th Century to Mainstream

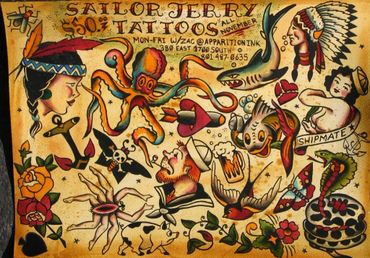

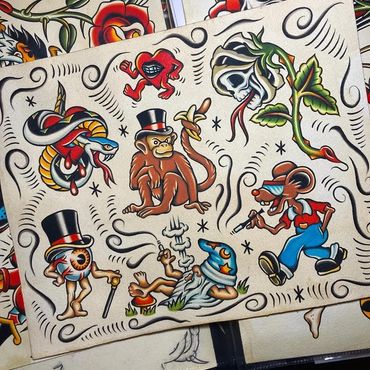

The mid-20th century marked a tattoo renaissance, driven by artists like Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins and Ed Hardy. Sailor Jerry, active in 1940s–1950s Hawaii, refined American Traditional with bold lines and nautical themes. Ed Hardy, blending Sailor Jerry’s style with Japanese irezumi, elevated tattooing to fine art. Celebrities like Janis Joplin and Cher in the 1960s and 1970s helped destigmatize tattoos, making them cultural symbols.

By the 1980s and 1990s, tattoos entered mainstream culture, fueled by media like *Miami Ink* and celebrity trends, such as Pamela Anderson’s barbed-wire tattoo. Tribal tattoos, inspired by Maori and Polynesian designs, surged in popularity, though their use raised concerns about cultural appropriation.

Contemporary Tattoo Styles and Trends

Tattooing is now a global art form, with diverse styles reflecting personal and cultural expression

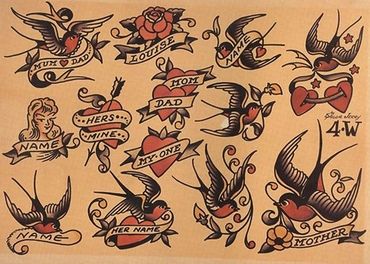

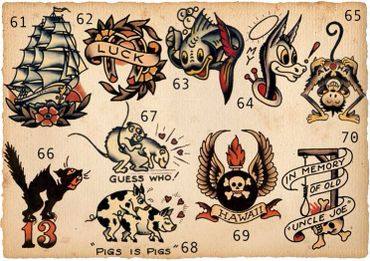

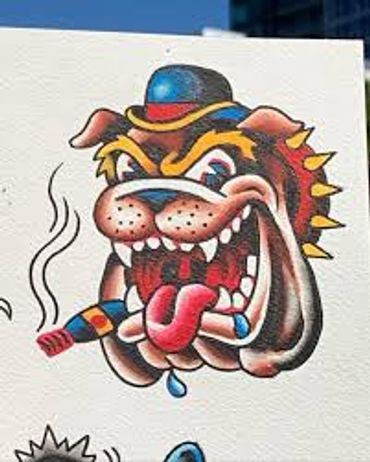

American Traditional Bold lines, bright colors, and iconic imagery (e.g., roses, eagles) remain timeless for their durability.

Japanese Traditional (Irezumi): Full-body designs with mythical creatures emphasize storytelling and harmony.

Neo-Traditional Blending classic and modern, it features vibrant colors and illustrative elements.

Tribal and Maori Bold, black, geometric designs carry cultural significance, though their Western use sparks ethical debates.

Fine Line Popular since the 2010s, these delicate, minimalist designs suit small placements like fingers.

Black and Gray Realism Photorealistic portraits with monochromatic shading create dramatic effects.

Color Realism Vibrant, lifelike depictions of subjects like animals or landscapes.

Surrealism Dreamlike, abstract designs combine imaginative elements.

Commemorative Tattoos Honoring loved ones or milestones, cited by 69% of tattooed Americans.

New School Emerging in the 1980s–1990s, this cartoonish style, inspired by pop culture, features exaggerated designs and sharp imagery.

The FUTURE OF TATTOING

Tattooing is now mainstream, with 30% of Americans tattooed by the 2010s. Technological advances like wireless tattoo machines and iPads help with design and improved sanitation, enhances safety and creativity thrives. Social media platforms like Instagram amplify artists’ reach, while shows like *Ink Master* cement tattooing’s cultural status. Emerging trends include bio-hacker tattoos for medical purposes and scalp micropigmentation for hair loss. Indigenous communities, particularly in the Philippines, are reviving traditional practices like batok. However, ethical concerns about cultural appropriation and commercialization persist.

Tattooing’s journey from Ötzi’s therapeutic lines to the vibrant Psyclon designs of today reflects its adaptability and cultural significance. Across history, tattoos have marked identity, spirituality, and rebellion, evolving from sacred rituals to mainstream art. As technology and societal attitudes advance, tattooing continues to innovate, blending tradition with modernity. Whether through the bold simplicity of American Traditional or the glowing surrealism of Psyclon, tattoos remain a powerful canvas for human stories, etched in ink.

REFERENCES

1. Deter-Wolf, A., & Diaz-Granados, C. (2013). *Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America*. University of Texas Press.

2. Friedman, R. (2019). *The World Atlas of Tattoo*. Yale University Press.

3. Krutak, L. (2014). *Tattoo Traditions of Native North America: Ancient and Contemporary Expressions of Identity*. LM Publishers.

4. Lodder, M. (2015). *Tattoo: An Art History*. I.B. Tauris.

5. Rush, J. A. (2005). *Spiritual Tattoo: A Cultural History of Tattooing, Piercing, Scarification, and Body Modification*. Frog Books.

6. Schildkrout, E. (2004). “Inscribing the Body.” *Annual Review of Anthropology*, 33, 319–344.

7. Thompson, B. (2015). *Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women, and the Politics of the Body*. NYU Press.

8. Wilcken, L. (2010). *Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern*. Schiffer Publishing.

9. “Ötzi the Iceman’s Tattoos.” South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. http://www.iceman.it/en/tattoos/

10. “Tattooing in Polynesia.” Polynesian Cultural Center. https://www.polynesia.com/tattooing

11. Pew Research Center. (2010). “Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next.” https://www.pewresearch.org

12. Instagram tattoo artist communities and posts (accessed via web search, August 20, 2025).

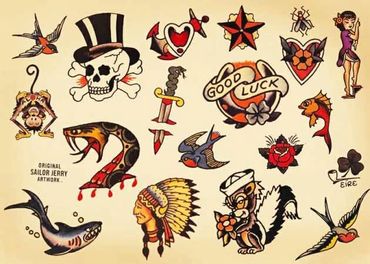

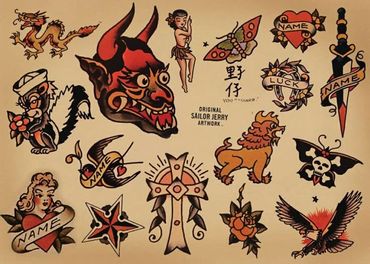

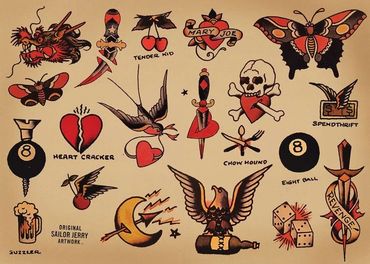

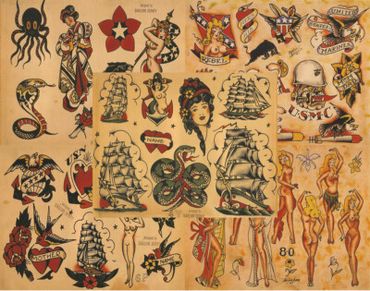

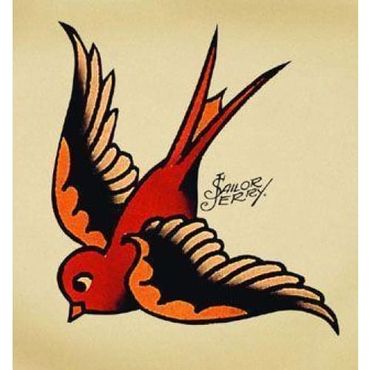

Norman

The OG ink legend with a legacy spanning decades, this icon of American traditional tattooing brought bold lines, vibrant colors, killer nautical vibes to life. From saucy pin-ups to fierce eagles and anchors, Jerry’s designs pop with timeless swagger. Even though he’s long gone, his style—rooted in old-school grit and sailor spirit—still slaps hard, crafting custom pieces with a wink and a smirk. Check out some of his old flash work here

OLD IRONSIDES

OLD IRONSIDES

OLD IRONSIDES

OLD IRONSIDES

OLD IRONSIDES

OLD IRONSIDES

SAILOR JERRY's LEGACY

Look back into time and catch a quick glimpse of how tattooing got its roots in American culture

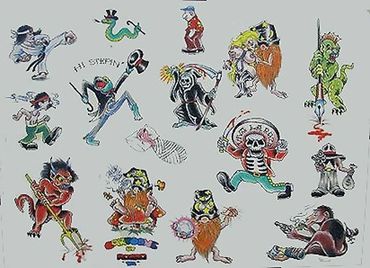

MIKE MALONE

Disatinctive stle also known as Rollo Jones and inventor of the rolomatic tattoo machine. popular for designing tpes of flash tattoed in the areas of

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLOMATIC

ROLLO BANKS

Look into Mike Malones presence in the industry and his infamous cutback Rollomatic tattoo machine